In May 2018, a phenomenon surfaced that lends itself of differential interpretation – some people hear “Laurel” whereas others hear “Yanny” when listening to the same clip. As far as I’m concerned, this is a direct audio analogue of #thedress phenomenon that surfaced in February 2015, but in the auditory domain. Illusions have been studied by scientists for well over a hundred years and philosophers have wondered about them for thousands of years. Yet, this kind of phenomenon is new and interesting, because it opens the issue of differential illusions – illusions that are not strictly bistable, like Rubin’s vase or the Duckrabbit, but that are perceived as a function of the prior experience of an organism. As such, they are very important because it has long been hypothesized that “priors” (in the form of expectations) play a key role in cognition, and now we have a new tool to study their impact on cognitive computations.

What worries me is that this analogy and the associated implications were lost on a lot of people. Linguists and speech scientists were quick to analyze the “spectral” (as in “ghosts”) properties of this signal – and they were quite right with their analysis – but also seemed to miss the bigger picture, as far as I’m concerned, namely the directly analogy to the #dress situation mentioned above and the deeper implication of existence of differential illusions. The reason for that is – I think – that Isaiah Berlin was right when he stated:

“The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing.”

The point of this classification is that there are two cognitive styles by which different people approach a problem: Some focus on one issue in depth, others connect the dots between many different issues.

What he didn’t say is that there is a vast numerical discrepancy between these cognitive styles, at least in academia. Put bluntly, hedgehogs thrive in the current academic climate whereas foxes have been brought to the very brink of extinction.

Isiah Berlin was right about the two types of people. But he was wrong about the relative quantities. It is not a one-to-one ratio. So it shouldn’t be “the hedgehog and the fox”, it should be “the fox and the hedgehogs”, at least by now…

It is easy to see why. Most scientists start out by studying one type of problem. In the brain – owed to the fact that neuroscience is methods driven and it is really hard to master any given method (you basically have to be MacGyver to get *any* usable data whatsoever) – this usually manifests as studying one modality such as “vision”, “hearing” or “smell” or one cognitive function such as “memory” or “motor control”. Once one starts like that, it is easy to see how one could get locked in: Science is a social endeavor, and it is much easier to stick with one’s tribe, in particular when one already knows everyone in a particular field, but no one in any other field. Apart from the social benefits, this has clear advantages for one’s career. If I am looking for a collaborator, and I know who is who in a given field, I can avoid the flakes and those who are too mean to make it worthwhile to collaborate and seek out those who are decent and good people. It is not always obvious from the published record what differentiates them, but it makes a difference in practice, so knowing one’s colleagues socially comes with lots of clear blessings. In addition, literatures tend to cite each other, silo-style, so once one starts reading the literature of a given field, it is very hard to break out and do this for another field: People tend to use jargon that one picks up over time, but that is rarely explicitly spelled out anywhere. People have a lot of tacit knowledge (also picked up over time, usually in grad school) that they *don’t* put in papers, so reading alien literatures is often a strange and trying experience, especially when compared with the comforts of having a commanding grasp on a given literature where one already knows all of the relevant papers.

Many other mechanisms are also geared towards further fostering hedgehogs: One of them is “peer-review”, which must be nice because it is de facto review by hedgehog, which can end quite badly for the fox. Just recently, a program officer told me that my grant application was not funded because the hedgehog panel of reviewers simply did not find it credible that one person could study so many seemingly disparate questions at once. Speaking of funding: Funding agencies are often structured along the lines of a particular problem, for instance in the US, there is no National Institute of Health – there are the National Institutes of Health, and that subtle plural “s” makes all the difference, because each institute funds projects that are compatible with their mission specifically. For instance, the NEI (the National Eye Institute) funds much of vision research with the underlying goal of curing blindness and eye diseases in general. But also quite specifically. And that’s fine, but what if the answer to that question relies on knowledge from associated, but separate fields (other than the eye or visual cortex). More on this later, but a brief analogy might suffice to illustrate the problem for now: Can you truly and fully understand a Romance language – say French – without having studied Latin? Even cognition itself seems to be biased in favor of hedgehogs: Most people can attend to only one thing at a time, and can associate an entity with only one thing. Scientists who are known for one thing seem to have the biggest legacy, whereas those with many – often somewhat smaller – disparate contributions seem to get forgotten at a faster rate. In terms of a lasting legacy, it is better to be known for one big thing, e.g. “mere exposure“, “cognitive dissonance“, “obedience” or the ill-conceived and ill-named “Stanford Prison Experiment“. This is why I think all of Google’s many notorious forrays to branch out into other fields have ultimately failed. People so strongly associate it with “search”, specifically that their – many – other ventures just never really catch on, at least not when competing with hedgehogs in those domains, who allocate 100% of their resources to that thing, e.g. FB (close online social connections – connecting with people you know offline, but online) eviscerated G+ in terms of social connections. Even struggling Twitter (loose online social connections – connecting with people online that you do not know offline) managed to pull ahead (albeit with an assist by Trump himself), and there was simply no cognitive space left for a 3rd, undifferentiated social network that is *already* strongly associated with search. LinkedIn is not a valid counterexample, as it isn’t as much a social network, as it formalized informal professional connections and put them online, so it is competing in a different space.

So the playing field is far from level. It is arguably tilted in the favor of hedgehogs, has been tilted by hedgehogs and is in danger of driving foxes to complete extinction. The hedgehog to fox ratio is already quite high in academia – what if foxes go extinct and the hedgehog singularity hits? The irony is that – if they were to recognize each others strengths – foxes and hedgehogs are a match made in heaven. It might even be ok for hedgehogs to outnumber foxes. A fox doesn’t really need another fox to figure stuff out. What the fox needs is solid information dug up by hedgehogs (who are admittedly able to go deeper), so foxes and hedgehogs are natural collaborators. As usual, cognitive diversity is extremely useful and it is important to get this mix right. Maybe foxes are inherently rare. In which case it is even more important to foster, encourage and nurture them. Instead, the anti-fox bias is further reinforced by hyper-specific professional societies that have hyper-focused annual meetings, e.g. VSS (the vision sciences society) puts on an annual meeting that is basically only attended by vision scientists. It’s like a family gathering, if you consider vision science your family. Focus is important and has many benefits – as anyone suffering from ADD will be (un)happy to attest, but this can be a bit tribal. It gets worse – as there are now so many hedgehogs and so few remaining foxes, most people just assume that everyone is a hedgehog. At NYU’s Department of Psychology (where I work), every faculty member is asked to state the research question they are interested in, on the faculty profile page (the implicit presumption is of course that everyone only has exactly 1, which is of course true for hedgehogs and works for them. But what is the fox supposed to say? Even colloquially, scientists often ask each other “So, what do you study”, implicitly expecting a one-word answer like “vision” or “memory”. Again, what is the fox supposed to say here? Arguably, this is the wrong question entirely, and not a very fox-friendly one at that). This scorn for the fox is not limited to academia; there are all kinds of sayings that are meant to denigrate the fox as a “Jack of all trades, master of none” (“Hansdampf in allen Gassen”, in German), it is common to call them “dilettantes” and it is of course clear that a fox will appear to lead a bizarre – startling and even disorienting – lifestyle, from the perspective of the hedgehog. And there *are* inherent dangers of spreading oneself too thin. There are plenty of people who dabble in all kinds of things, always talking a good game, but never actually getting anything done. But these people give just give real foxes a bad name. There *are* effective foxes, and once stuff like #Yannygate hits we need them to see the bigger picture. Who else would? Note that this is not in turn meant to denigrate hedgehogs. This is not an anti-hedgehog post. Some of my closest friends are hedgehogs, and some are even nice people (yes that last part is written in jest, come on, lighten up). No one questions the value of experts. We definitely need people with a lot of domain knowledge to go beyond the surface level on any phenomenon. But whereas no one questions the value of keeping hedgehogs around, I want to make a case for keeping foxes around, too – even valuing them.

What I’m calling for specifically, is to re-evaluate the implicit or explicit “foxes not welcome here” attitude that currently prevails in academia. Perhaps unsurprisingly, this attitude is a particular problem when studying the brain. While lots of people talk a good game about “interdisciplinary research”, few people are actually doing it and even less are doing it well. The reason this is a particular problem when studying the brain is that complex cognitive phenomena might cut across discipline boundaries, but in ways that were unknown when the map of the fields was drawn. To make an analogy: Say you want to know where exactly a river originates – where its headwaters or source are. To find that out, you have to go wherever the river leads you. That might be hard enough, just like when Theodore Roosevelt did this with the “River of Doubt”, arguably all phenomena in the brain are a “river of doubt” in their own right, with lots of waterfalls and rapids and other challenges to progress. We don’t need artificial discipline or field boundaries to hinder us even further. We have to be able to go wherever the river leads us, even if that is outside of our comfort zone or outside of artificial discipline boundaries. If you really want to know where the headwaters of a river are, you simply *have to* go where the river leads you. If that is your primary goal, all other considerations are secondary. If we consider the suffering imposed by an incomplete understanding of the brain, reaching the primary objective is arguably quite important.

To mix metaphors just a bit (the point is worth making), we know from history that artificially imposed borders (without regard for the underlying terrain or culture) can cause serious problems long term problems, notably in Africa and the Middle East.

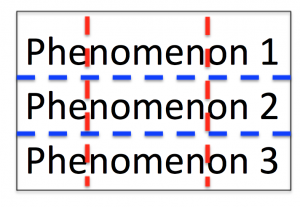

All of this boils down to an issue of premature tessellation:

The tessellation problem. Blue: Field boundaries as they should be, to fully understand the phenomena in question. Red: Field boundaries, as they might be, given that they were drawn before understanding the phenomena. This is a catch 22. Note that this is a simplified 2D solution. Real phenomena are probably multidimensional and might even be changing. In addition, they are probably jagged and there are more of them. This is a stylized/simplified version. The point is that the lines have to be drawn beforehand. What are the chances that they will end up on the blue lines, randomly? Probably not high. That’s why foxes are needed – because they transcend individual fields, which allows for a fuller understanding of these phenomena.

What if the way you conceived of the problem or phenomenon is not the way in which the brain structures it, when doing computations to solve cognitive challenges? The chance of a proper a priori conceptualization is probably low, given how complicated the brain is. This has bothered me personally since 2001, and other people have noticed this as well.

This piece is getting way too long, so we will end these considerations here.

To summarize briefly, being a hedgehog is prized in academia. But is it wise?

Can we do better? What could we do to encourage foxes to thrive, too? Short of creating “fox grants” or “fox prizes” that explicitly recognize the foxy contributions that (only) foxes can make, I don’t know what can be done to make academia a more friendly habitat for the foxes among us. Should we have a fox appreciation day? If you can think of something, write it in the comments?

PS: Of course, I expect no applause for this piece from the many hedgehogs among us. But if this resonates with you and you strongly self-identify as a fox, you could consider joining us on Facebook.

This article originally appeared at Pascal's Pensées

Pascal Wallisch, Ph.D did his undergraduate studies at the Free University of Berlin, received his PhD from the University of Chicago in late 2007, then worked as a research scientist at the Center for Neural Science at New York University and now serve as a Clinical Assistant Professor in the Department of Psychology.